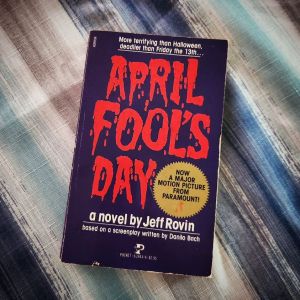

This post will unavoidably be filled with spoilers for both April Fool’s Day (1986) and the novelization of same by Jeff Rovin. So, if you haven’t at least seen the movie and have somehow managed to make it this far without knowing its notorious twist, then proceed with caution. Or better yet, go watch it – it’s a hoot!

April Fool’s Day is one of my favorite slasher films precisely because of the reason most other people don’t like it. For those who don’t know – or need to be reminded – the premise of April Fool’s Day is classic And Then There Were None. Wealthy heiress Muffy St. John has assembled a bunch of her college friends for a weekend on her family’s island, but it seems that someone is picking them off one by one.

The twist comes in the ending, when it is revealed that no one was actually killed. Indeed, it was all a sort of elaborate April Fool’s prank – a way for Muffy to try out a test run of her plan to turn the family homestead into a bed and breakfast offering murder mystery weekends. As each person was “killed” they were, instead, inducted into the game, and the film ends with a surprise party for the last one standing where all is revealed.

I love this for many reasons, not the least being that it makes the preceding film much less mean-spirited than many of its contemporaries, which rely on the assumption that audiences enjoy watching people be terrorized and murdered. This not only means that the whole shebang becomes relatively wholesome fun, but also frees the filmmakers from the “necessity” of making characters whose deaths the audience will root for.

While the kids in April Fool’s Day may still be rich, WASP-y horndogs, they’re fun to spend time with, and they seem like people who might actually be friends in real life, making them among the more enjoyable of slasher movie ensembles. Honestly, the flick may be at its most fun when we are simply watching them play pranks on one another early on, before the (fake) body count has begun.

The thing is: April Fool’s Day didn’t always end there. The original cut of the film continued on for about another reel, introducing an actual killer and a much more tragic ending, even if the killer wasn’t actually successful in increasing the body count beyond “one” – that being the killer himself.

The actual footage of this ending currently appears to be lost, despite some efforts to recover it for fancy Blu-ray releases. But that doesn’t mean it’s completely gone. There’s the novelization, also released in 1986 and written by Jeff Rovin, whose CV is considerable and varied but whose name is most familiar to me from writing those How to Win at Nintendo Games books that were ubiquitous when I was a kid.

It is de rigueur for movie novelizations to hit shelves around the same time that the movie does, which means that the writer is working from a screenplay, not from the finished product. This often means that novelizations contain scenes and other elements that differ from the final film. In the case of Rovin’s April Fool’s Day, it means that whole ending is still intact.

The place where the movie stops has arrived by around page 175, but the book continues on to page 222, retaining the entire second plot with the actual killer. Besides an opportunity to see at least somewhat how the probably lost ending would have played out, this also adds a second element to the movie. Producers obviously axed that ending after shooting was already at least mostly finished, and the conjuring trick of removing it isn’t entirely seamless.

Early on, Muffy appears to play jokes on everybody by leaving items in their rooms. Unlike the other pranks played throughout the film and book, these jokes are intensely personal and viciously cruel – especially the one left for Nan Youngblood, which references an abortion she secretly had. The movie provides no adequate explanation for these. Muffy apparently planted them, but there is no reason for her to have played a trick so needlessly and specifically cruel, even to further her murder game.

The lost ending provides that explanation. They aren’t the ones that Muffy planted. Oh, she planted jokes, alright, ones specifically tied to each character’s past, but not the ones that they find. Those were planted by the real killer, to give everyone there a motive for offing Muffy, thereby covering his tracks when he killed her in order to take her inheritance.

It’s all a bit convoluted but it at least goes some distance toward explaining away an element that is otherwise incongruous. Was the movie better with the full ending? For that matter, is the book? Probably not, but the book pulls both endings off pretty well, and it’s interesting to have a record of the way things might have gone.

In fact, the whole book is pretty good, albeit odd for a number of other reasons, not least Rovin’s unusual pedigree, as already mentioned. But perhaps the most distracting one is the amount of product placement that goes on in its pages. Anytime it is possible to mention a brand name, you can bet that Rovin does so, and sometimes he goes out of his way to create an opening. Was product placement in novels even a thing? I have no idea, but something sure got him dropping brand names left, right, and sideways.